By many accounts, English is becoming the “lingua franca” of the 21st century. Certainly, it is the language of business and academia, leading some to argue that there is no longer any need for native English speakers to study other languages. This sentiment is reflected in data from ACE’s

Mapping Internationalization on U.S. Campuses study that indicate a steady decline over the last decade in the percentage of institutions that require foreign language study for graduation:

At those institutions that do have a foreign language study requirement, at nearly half, it is for one year of study or the equivalent. Only 2% of institutions require more than 2 years or the equivalent.

Like courses that focus on particular countries or regions,

foreign language study provides important cultural and contextual knowledge that enables a more in-depth and nuanced understanding of global issues and how they play out in different areas of the world. And while students around the globe study English, the quality of instruction and length of study vary considerably – it cannot be assumed that everyone American graduates will encounter in the future will have attained a high level of English proficiency. Learning a foreign language can help U.S. students meet their non-native English speaking colleagues "half way," and

pave the way for more meaningful interactions, successful business transactions, and academic collaborations.

In making the case for foreign language study,

Dr. Suzanne Shipley, President of Shepherd University, states:

"As long as we ignore the need for Americans to become familiar with a foreign language as part of high school or college study, we dilute the cultural experience possible with internationalization. Global learning requires empathy, and that empathy arises from communication.

"Our students may become familiar with a culture's history, traditions, economy, and political structure, but unless they acquire at the very least minimal familiarity with its language, they will not gain access to the country's true identity. Because as Americans we are no longer exposed to foreign languages, we find it ever more difficult to understand other cultures."

Among those institutions that have maintained a commitment to foreign language study, there are a

variety of models for requirements, tracks, and venues. In some cases, the language study requirement is considered part of

general education requirements; in others, it stands on its own. ACE’s

Mapping data indicate that a large majority (76% in 2011) of institutions allow students to

“test out” of taking language courses by demonstrating prior proficiency – models include the use of AP scores and placement tests administered by language departments.

Institution-Wide Foreign Language Requirements

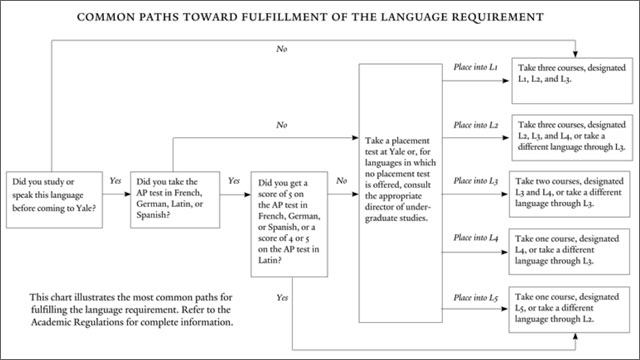

As illustrated in the chart below,

Yale University’s language requirement allows students to test into higher level courses, but still requires all students, regardless of prior proficiency, to take at least one foreign language course:

Responding to the needs of its student population, Florida International University (FIU) has developed two separate “tracks” for students who wish to study Spanish to fulfill the institution’s

foreign language requirement – one for “heritage learners” and one for “non-Heritage” learners. FIU’s

Department of Modern Languages website defines heritage learner and outlines the 2 tracks.

Cultures and Languages Across the Curriculum (CLAC)

The Cultures and Languages Across the Curriculum (CLAC) Movement intends to make global competence a reality for students and to create alliances among educators to share practices and find ways to incorporate an international dimension in curricula, and, more generally, to achieve internationalization goals. According to its

website, general principles of CLAC include:

- A focus on

communication and content.

- An emphasis on developing meaningful content-focused language use

outside traditional language classes.

- An approach to language use and cross-cultural skills as means for the achievement of

global intellectual synthesis, in which students learn to combine and interpret knowledge produced in other languages and in other cultures.

The

CLAC website provides details about the various forms CLAC can take within the curriculum, a discussion blog, information for faculty and institutions seeking to implement CLAC initiatives, and descriptions of CLAC programs at a number of

institutions.

One more level to go!

The next installment of Internationalization in Action will look beyond individual institutions, examining broader efforts to internationalize curriculum at the

discipline level. We’ll also take a look at how all this comes together, and how to

assess student global learning. Stay tuned!