Note: This is a transcript, edited lightly for length and clarity, from a session conducted April 14, 2023, at ACE2023, ACE's Annual Meeting in Washington, DC.

For more context around this session and the race in admissions cases before the Supreme Court, click here.

Panelists: Ishan K. Bhabha, Partner and Co-chair, Education Practice, Jenner & Block; Art Coleman, Managing Partner and Co-founder, EducationCounsel LLC ; Shannon Gundy, Assistant Vice President, Enrollment Management, University of Maryland, College Park; Moderator: José Padilla, President, Valparaiso University.

José Padilla: We're going to talk about a door closing. The door was opened 45 years ago in the Bakke decision that you might have heard of. And it's interesting, it came down in 1978, about two years before I entered as a first-year law student at the University of Michigan Law School. I have no doubt that the University of Michigan took into consideration the fact that I was a Mexican American kid from Cleveland, Ohio, and it got me into law school. I think other things got me in law school, but I have no shame in the fact that they took me, me being Latino and I'm glad that they did. And the Supreme Court reaffirmed this decision in Bakke in 2003, in the Gratz and Grutter decisions, and then subsequently in two decisions against the University of Texas brought by a plaintiff named Fisher.

And now we're at this point in time where it looks as if the door is slowly but surely closing and most likely will close. And obviously we're going to be in a situation where we don't know whether or not we can take race and ethnicity into account in college admissions as well as other issues on campus.

I have a murderer's row of panelists, some of the best minds in the country on admissions and legal issues surrounding enrollment issues. From my far right, Shannon Gundy, who is the assistant vice president for enrollment management at the University of Maryland, where she's been for 33 years.

Shannon Gundy: I was two when I started.

José Padilla: And then to her left is Ishan Bhabha, who is a partner at Jenner & Block, and co-director of the education practice. He clerked for the Supreme Court for then Justice Kennedy as well as for Merrick Garland, who now is the Attorney General. To his left is Art Coleman who's the managing partner and co-founder of the EducationCounsel. And like me, he was a political appointee in the Clinton administration as the deputy assistant secretary for Civil Rights in the Department of Education. They bring a lot of insight, but I want you to know is that when this presentation is over with, we want to hear from you as well.

Before I go and turn over to the panel, give me a flavor the room. How many folks here are presidents or provosts? Okay. How about a person who deals with diversity, equity and inclusion issues? Okay. Financial aid? Admissions? No one here in admissions, one person. You're not ashamed of being here? (laughter)

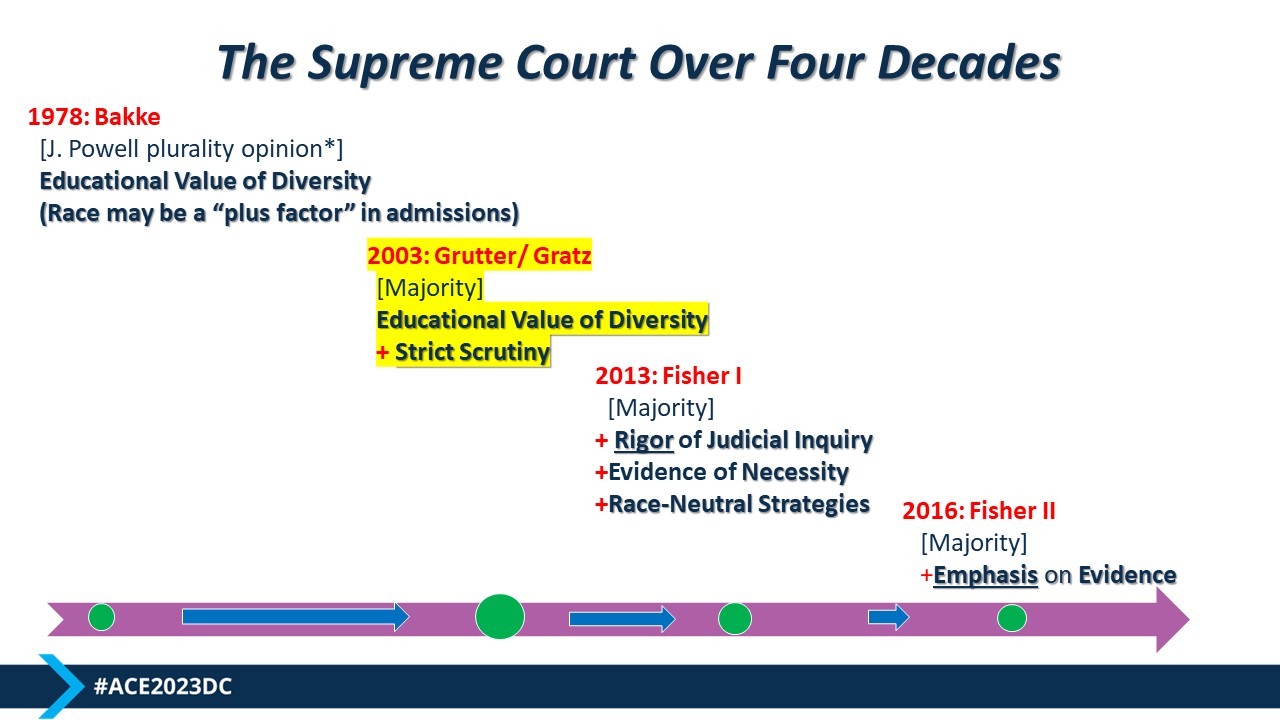

José Padilla: So now what I want to do is get to this slide, and Art is going to tell us how we got here at this point in time from that decision in Bakke 45 years ago.

Art Coleman: Good afternoon, everyone. You'll all get your JD after this one slide, this is the history in a nutshell. José alluded to this, for 45 years we've had a remarkably consistent body of case law that has affirmed that the educational benefits of diversity can support a limited consideration of race through holistic review and admissions. Period, end of sentence. Cases have gone up, cases have gone down. But the court has maintained that very consistent focus on that fundamental theory that establishes this foundation for the consideration of race in admissions.

One of the things I just want to lift up in this context, one of my soapboxes is you're going to hear this referred to as affirmative action in all of the media. In fact, the Supreme Court is probably going to refer to it as affirmative action. It's not. This is not remedial. This is not backward looking. This is not correcting some past inequities even though it intersects the issues of inequities. It is a forward-looking, mission driven, educationally grounded theory on which institutions have relied based on the nugget that Justice Powell gave us in 1978. So just an important grounding as we talk about the issues here. Remember, it's really tied to a mission and what you are trying to achieve institutionally with respect to your diversity, equity, and inclusion.

José Padilla: Shannon, you've been an enrollment professional for all these years and now we're at this point in time, give an idea of what it's like on the ground and in terms of recognizing what may transpire in the court and how you and your colleagues are thinking about it at this time.

Shannon Gundy: I think it's interesting. This one feels a little bit different. I've been doing this long enough to have gone through not all of those cases, but a good number of them and the feeling is very different. I think there's a feeling of foreboding, there's a pall that's passed over what we do. I don't think that there are very many people who think that there won't be something drastically different about the way we do our business as a result of these cases that have been heard and we're waiting for the decisions for.

I think we should understand that what we are trying to accomplish is being attacked. As an African American woman, it's the case that it's not just professional for me, it feels personal. It feels like we are really working to try to do very good work. We are trying to ensure that education is accessible to people who really need it the most. But it feels like there are continual attacks that are happening regarding the work that we do.

It's also the case that those of us that have been doing this for a while know that whatever the results of this case are, there's going to be an awful lot of work to be done. We are not going to stop working toward the goals that have been established that are part of the missions of our institutions, but we are likely going to have to find different ways to achieve the goals that are important to us. So there's an awful lot of work, there's a lot of cost involved. So understanding what the future holds means that this isn't the happiest time to work in the world of admissions.

The other thing that I think we have to give thought to is how this is not only going to impact the work that we do, but the students that we've worked with. I've had conversations with currently enrolled college students, with prospective college students who are all very worried about what this is going to mean for them. So it is very much a very different world than the worlds that we lived in with previous cases.

José Padilla:: Thank you. Ishan, can you describe what the issues are in these two cases?

Ishan Bhabha: Sure. Good afternoon, everybody. Very nice to be here. So the two cases which were argued at extraordinary length on Halloween, and which we are likely to get the decision on in June, pose the question of -- for the University of North Carolina, obviously a public school and for Harvard, a private school -- whether or not the explicit consideration of race in admissions is permissible. For UNC, this comes under Equal Protection Clause as a public entity which is responsible for and is accountable to the Bill of Rights, and equality and development. And for Harvard, it comes under Section VI of the Civil Rights Act as a recipient of the federal funds.

So let's just unpack that a little bit. Again, I said the explicit consideration of race in college admissions. That means an enormous amount, but there are also things it doesn't. What the court is being asked to determine is whether or not the holistic analysis that, as Art mentioned, has governed for almost 50 years. Whether that analysis which takes into account race not as a thumbs up, thumbs down mechanism, but part of an overall assessment--is that still permissible? And when the court makes its ruling, if it says no, which I think many commentators who are going to talk about it admit is a possible outcome, it's going to affect admissions directly, but there are a whole variety of things that it's not going to affect.

So number one, do you give it direct consideration? That doesn't mean implicit consideration. That doesn't mean consideration of factors which may be correlated to race. And likely, it's about college admissions. It's not about everything else. We're going to get into all of that in a minute, but that is the basics of this. During the admission decision, can an institution, public or private, lawfully consider the race of an applicant as part of the admission?

José Padilla: Thank you. We have a tape of Justice Coney Barrett's, one of the comments during oral arguments .

Art Coleman: So there's obviously a question of what is the court going to do? And any lawyer worth their salt is not going to sit up here and give you a definitive prediction. There's no predicting this court. I will tell you, I think it is fairly safe to say this court did not take the UNC and Harvard cases to tread water. They took Harvard directly off the First Circuit Court of Appeals and then reached down and blocked the UNC case from the district court, bypassing the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. So there is energy by the court.

But you might say, "Gee, it was only seven years ago that the University of Texas prevailed on these very same issues. What's the difference?" In large part, it's the composition of the court. You have four justices on the court today that were not on the court in 2016 when the UT case was decided. And more to the point, of the five justices who were on the court, there was only one who was part of the majority at the time. So you've got a dramatic shift in the composition of the court as a consequence of various appointments that have been made.

The question is what's going to happen? I think going with conventional wisdom, which I believe, that the results are not going to be favorable to higher education. I think there are a lot of people who, and you've probably already read this, affirmative action is dead. It's all but the funeral, which will occur in late June by some estimates. I tend to be slightly more optimistic than that gloom-and-doom pessimism. I consider that, the total Armageddon of an outcome. I think there's a tsunami which is slightly less bad that we can navigate. SFFA, the plaintiff in these cases, conceded that it was not seeking to eliminate the ability of an applicant to tell their full authentic story even when that story could include express discussion of their racial experience, their lived experience, their perspective, or their goals.

And so if you step back for a second and think through, wow, that seems to be the totality of what a student would say in an essay or what teachers might write in a recommendation. There's a lot that could be preserved if the court accepts that concession. The quote we looked at, I want to raise as one of four or five over the course of five hours of oral argument. This court went back and back and back to that line drawing. They wanted to understand how SFFA was conceding this line to potentially avoid a total wipe out in this context. And what they ultimately got to was the notion of SFFA saying, we want all elimination of any status determination based on stereotype, based on assumption, that kind of check the box mentality. I see you're a student of color, therefore that's an impermissible practice. But they contrasted that again with this authentic storytelling about an applicant's lived experience and perspective, that Shannon can tell you better than I, is much more central to holistic review in admissions.

That check the box term was used over 30 times in the course of five hours of oral argument. That tells you how this court is focused on that. And so I have some fervent hope that we could actually avoid the Armageddon, and the court might say, eliminate all consideration of racial status when you're making assumptions or stereotypes about students without more, but we're not going to eliminate their ability to tell the full story about them.

José Padilla: Ishan, what did you divine from the oral arguments?

Ishan Bhabha: I agree with everything Art said. I think to wear here my dorky lawyer hat here, I'm advising as I'm sure lots of us are, numerous colleges and universities who are faced with a question of what do I do? And we're going to talk about that in detail.

But it's helpful, I think, to pull apart the two legal principles that are really at stake here within the analysis the court is going to conduct. So when you're considering race in any facet of American society, it falls under the most exacting scrutiny, what the court calls strict scrutiny. And if there is strict scrutiny, an entity in order to satisfy using a racial preference needs to number one, have a compelling interest. And then the means in which race is taken into account have to be narrowly tailored to that compelling interest. So you have two things, the compelling interest and narrow tailoring.

And so what we think about what the court is going to say in this case, and I agree with Art…I think it's likely that the schools in these issues are to lose. And there are two ways they could lose, and I think it's going to have different implications. The court could say, diversity in higher education is no longer a compelling interest. That is just not something we are going to recognize no matter what this school does in aid of it, it's not a compelling interest. That would, I think be what Art talked about as the Armageddon. That really will strike at the heart of a lot of not only admissions issues, scholarships, affinity groups, DE&I initiatives, a whole host of that. I think there may be some votes on the court for that. I don't think there are five.

But I think the more likely outcome is the court says, "Look, even if diversity is a compelling interest writ large, the way it is being operated now to affirmative action is not narrowly tailored." And for any of you who listened to even a few moments of the six hours of oral argument, you might have heard reference that the oboe player and the squash player.

Justice Gorsuch asked a number of questions about that. Why did he ask this question? Because what he was trying to demonstrate to the lawyers for the institutions was that, look, you have a whole set of admissions preferences and one of those sets of admissions preferences includes squash players, oboe players, lacrosse players, individuals who may overwhelmingly be white, middle class, upper class male for example, or female. He was saying it is not good enough for you to admit this group of individuals -- and you can add alumni children, donors and alike -- on the one hand. And at the same time, saying in order to then racially balance our class, we have to over index for race in another one. He said that doesn't count as narrow tailoring for him.

Obviously, I think there's going to be dissension, I think there's going to be people who disagree with that analysis, but to me listening to the questions and frankly, looking at some of the things that the justices have said, those who have written about these sorts of programs in the past. I think that quite a likely outcome is on the grounds of tailoring. And then really the devil is going to be in the detail.

The question is going to be for institutions nationwide, how do you react? We're helping schools already think about that today. Now, the question will be what are your institutional priorities? What do you want your classes to look like and how do you do that in a risk-adjusted way? And if there's one message in terms of what the court is likely to do, it's that overreactions very dangerous. To bury your head in the sand and say we're going to keep doing it, it's business as usual, I think is likely to put institutions in real legal jeopardy. And so if your admission system considers race in some way, you need to look at it carefully. But that doesn't mean jettisoning the entire project. It doesn't mean reading the worst possible implication and getting rid of anything at all. But it needs to be done in a really careful detail-oriented way, which requires rolling up your sleeves and working hard on it. But I think there are opportunities.

José Padilla: Thank you, Ishan. We're going to talk a little bit more about that later. All right. So now, what are the potential implications of this? And I'm going to ask Shannon first. You alluded to this a little bit in your opening statement, but what are your colleagues in enrollment management keenly thinking about now? What are they talking about and how are they going to react to this to deal with it?

Shannon Gundy: I think that there are a couple of schools of thought or action, more appropriately. I think there are those who are really trying to be prepared as best they can, meaning that schools maybe pulling together people to have conversations about this, identifying how we need to be moving forward, noting what we need to be paying attention to when adjustments will need to be made ultimately. And then there are others who really are not doing much anything. I think there are lots of folks who are waiting to see what the outcome of the case is are going to be before they move forward, not wanting to do work until they know what work needs to be done, which I think is a little bit unnerving when I think about being in a position like that. I think that folks really need to be prepared in order to move forward.

But I think the overarching thought and feeling about all of this is that people are tired. This has the potential of being very demoralizing.

The good news in all of that is I think that those of us who are committed to doing this work are used to being challenged. We are used to people disagreeing with the way we do business and even disagreeing with the why in the way we do business. And I think that there is a commitment to continue to move forward because all of us know-- every single person in this room knows -- that the value of education exists to change lives. Beyond that, I think we need to understand that it's not just changing the lives of the individual but it changes lives of the entire family. It changes lives of the entire communities and our entire nation. And if we understand that we can be a better place, a better country because we are allowing access and ensuring access to higher education to communities that have been left out of the equation, I think that the commitment to continue to do this work will go on.

José Padilla: The defendants here Harvard, North Carolina, they're obviously pretty selective, clearly Harvard is. Is this only a problem for the highly selective schools?

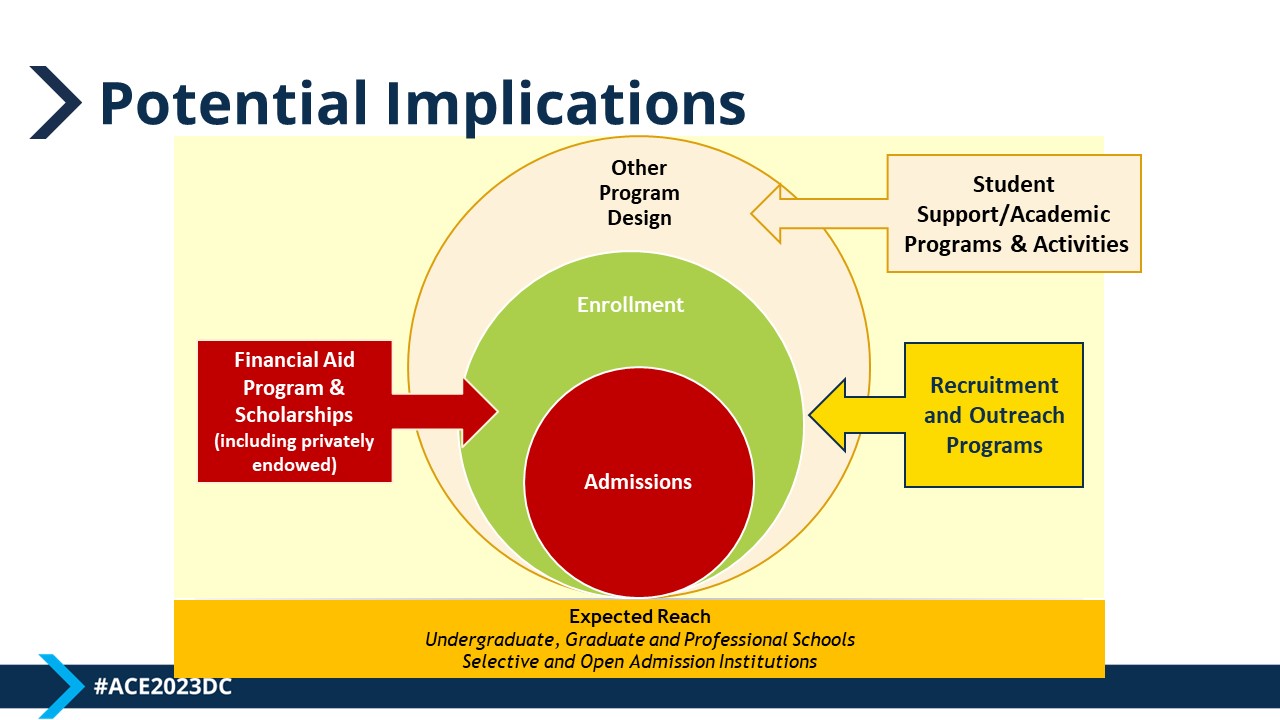

Art Coleman: I don't think so, and this visual helps explain that tale. We're not going to sit here and predict with certainty what the court's going to do. I can predict with absolute confidence, the reach of this decision will go beyond undergraduate admissions to graduate and professional school admissions. Remember, Grutter was a law school case, Bakke was a medical school. I don't expect distinctions there.

But I think the important point I would make here is beyond those institutions that may not be selective in admissions, you likely have policies and programs that at least should be on your radar, at least should be part of an inventory that you're collecting now to at least know what the baselines are for preparation for a consequentially adverse decision that we are all expecting. In particular, that is true with respect to issues of financial aid and scholarships where you have race-conscious scholarships in financial aid. In that case, yes this is an admissions case. There's nothing in the record and nothing in the argument that suggests the court's going to go beyond the four corners of an admissions decision. But the court always starts with general principles. And if they are broad and sweeping—think an opinion by Thomas or Alito, for instance—he implications and the ripple effects might legitimately be felt with respect to race-conscious financial aid and scholarships are profound.

Particularly if you go back to the line that Ishan and I both believe the court might tow, which is to say, get rid of check the box racial status determinations but maintain this authentic holistic review. How do you make race conscious scholarship and financial aid decisions? Not typically with holistic review. It is usually looking for students who qualify, students of color who can then otherwise fit the criteria of your scholarship or financial aid. So I think the implications here are potentially bigger and broader than just admissions, and we should be thinking in a proactive way now so that we are ready for the implications there if in fact they come.

José Padilla: How many of your schools actually require detailed letters from the applicants in support of their admissions package? At Valparaiso University, we don't. And when I was at DePaul University, we had 25,000 students. They just couldn't do it. So we never did that.

Now Ishan, can you talk to the audience about the distinctions between those schools that require those kinds of letters in which an applicant can tell you directly or indirectly what their race or ethnicity are versus the schools that don't do that? Are we going to basically have to require these kinds of letters in order to try to, in a backdoor kind of way, define who these students are?

Ishan Bhabha: This is a great question. I think this is where the rubber's going to hit the road. So as I said, I think the decision is going to really talk about the explicit consideration of race. So the next case, and there are going to be numerous cases going forward, is going to look at what happens when a school makes admissions decisions in a way that may be correlated to race in some way but are not defined by race in particular. And in fact, we don't need to wait that long for that case to come.

Those of you who are from the District of Columbia or from this area maybe familiar with Thomas Jefferson High School. Their admissions policies are being challenged right now because there is the allegation that they basically do exactly this. They don't consider race explicitly, but in fact, everything that they are making these admissions decisions on is correlated to race. In that case, the school lost in the district court. The school won a stay of the decision while it is appealed.

More broadly to the question the slide captures this, I think really in three concentric circles. So you have the admissions decision itself, that I think is going to be ruled on by the court in June. One concentric circle out, you have everything that happens pre-admissions and you have everything that happens post admission. That, the court will not rule on in June. That is not the issue before the court, but that's certainly coming. And then I think you have the broader category which Art alluded to, which is everything else. It's scholarships, it is mentorship programs, it's DE&I initiatives. That is not in this case but it is coming.

And so I think when you think about what sort of information you're soliciting from your students or your applicants, my advice to our clients is this is a place you can be creative and you can lean in like that. The law isn't prohibiting you from doing that. It may but it isn't today. And so you need to look at your own institution, you need to look very carefully in your admissions procedures and decide what your level of risk tolerance is. But I think it's those sorts of things that allow an applicant to tell their full stories. And the institution, to be clear, it has to live by its values. It cannot be -- and I think the law will not permit -- just consideration of race by another means. If you believe in the value of, for example, thriving in an environment around individuals who are different from you, one metric of that is ethnicity, another might be rural, another might be based upon socioeconomic status. And so the institution actually has to do that.

But I think by engaging in this more multifaceted analysis, to go back to Art's initial point, this doesn't mean that diversity in college admissions is dead. It just needs to happen in a different way.

José Padilla: If you're a small private, you probably don't have unlimited money for resources. And so, are you going to hire more readers if you're going to require a statement in support of the application package? And if you don't hire somebody, are you going to get alums to read the package? I'm not discounting what they're saying, but I'm just trying to raise some of the practical issues that will arise here. I believe, I'm going to be talking to my vice president of enrollment management, is there a way we can divine more information? Because I've told my folks, this is not going to deter us from trying to make our campus diverse and keep it diverse, but we're just going to have to be a lot more smart about it.

On the recruitment and outreach programs, I think you all are fairly confident that it still should be okay at least at this point in time by virtue of the issues in these cases. Correct?

Art Coleman: Yes. And I would just say here interestingly, because I think one of the questions that's really important from an institutional vantage is not just what might I not be able to do, but what can I do in the wake of an adverse decision that might help mitigate or ameliorate the adverse effects of a negative decision? Really stepping back and recalibrating on a lot of things.

The law, generally speaking, does it treat broad based recruitment and outreach the same way it treats race conscious admissions or race conscious financial aid because you're not conferring that individual benefit to a particular student based of their race. It's broader and in legal terms, it's deemed inclusive and not subject to these legal standards that Ishan just walked you through.

So the recruitment outreach piece, with some exceptions depending on discreet programs that I'm not going to get into, gives you a zone of opportunity to think more strategically, to think about doing more and better with race aware or race targeted recruitment and outreach, that doesn't rise to the level of race conscious outreach in the context of a potential impact.

Ishan Bhabha: And I think if you want to think about two different things that toggle here, to figure out if you're looking at a program, how permissible or how risky it is. One is to Art's point, how explicit is the consideration of race? That's one. The other one is how great is the benefit being conferred? Or looking from the other side, how easy would it be for somebody to challenge what you are doing who's not receiving that benefit? So in that respect, race conscious admissions is in some respects, the worst case because it is the explicit consideration of race and whether or not you get into a school or not, it's a very big benefit you're complaining about. So it's an easy case to bring.

Something like an outreach program where you may or may not be considering race in some way, would you be forcing somebody to say, "Look, I really wanted to go to Valparaiso, but I didn't get a brochure in the mail advertising Valparaiso, so I didn't apply, so I didn't go." That just doesn't sound like such a tangible claim. And in the legal terms, you would say the standing for the plaintiff there is a lot weaker. So that's why I think these other areas beyond the actual decision point right now, are places to really lean into.

José Padilla: Okay, let's get more granular on what we do in these two or so months while we're waiting for this decision for the door to close. I think Shannon, you were talking about some folks, they're obviously anxious and so forth, but what are you and your colleagues doing now?

Shannon Gundy: There are two things that I want to talk about here. One is what we are doing now is trying to get prepared. The uncertainty is that we don't know what we're preparing for, but we do know that we need to do a really good inventory of what we're already doing. We need to know where this decision could touch and what we're going to need to pay attention to and have some idea about how we move forward.

What we've done very practically, is pull together a group of people so that it's not just admissions thinking about this because admissions is not the only place on when our campus that's going to be impacted. We pulled together a pretty broad group of what I hope are really powerful minds. We pulled together a group that includes enrollment management, so it includes undergraduate as well as graduate admissions. We've included staff from our institutional research planning and assessment. We have one of the university attorneys as a part of this group, the vice president for diversity and inclusion is a part of this group. We have the university's chief communication officer is a part of this group.

Our intention is to be ready to hit the ground running when the decisions are released. We know that as an institution, regardless of what the outcome of the decisions will be, we want the public, we want our students, we want our faculty and staff to know that our mission has not changed.

We remain committed to diversity and we'll continue to work to ensure that we have a diverse student population at the university. The way that we need to do that and the way that we'll get there may change, but we want people to know that our commitment is not going to be waned as a result of the outcome of those cases. So we're having those conversations now and trying to get people on campus prepared, and trying to educate them about what we already do and we have them understand what our strengths are. I think we're coming from a very strong place and I want them to be very confident as we're moving forward. But I also want people to know that there are going to be resources that are needed to move forward. It's going to take time, it's going to take money and energy to continue to move forward after that. So I'm trying to lay the foundation so that the institutional commitment will be there when we need it to be there.

The other thing that I think people are not paying as much attention to is the fact that there's a whole lot of work that's going to need to be done in the K-12 community. When I have conversations with school counselors, often I'm finding they're not really aware of what we do and how we do it. They're not aware that if the Supreme Court says you can't use race in the check the box kind of fashion, but you can continue to use race in a holistic fashion when a student is telling you about themselves and how their race has impacted them. What that means is that we are going to have to educate students about how to write about who they are in a very different way than they do now.

Right now, students write about their soccer practice, they write about their grandmother dying. They write about the things that are personal to them. They don't write about their trials and tribulations, they don't write about the challenges that they've had to experience, and they don't know how to and they don't want to. We're going to have to educate students in how to do that.

We're going to have to educate school counselors about how to do that in their letters of recommendation. And we're talking about a population of people that is very, very overworked and underpaid as it is and are going to be very reticent. That's a world that we're going to have to be stepping into. So I think institutions also need to be thinking about how they're going to assist the high school community in getting them prepared to move forward after these decisions are released.

José Padilla: Shannon raised the fact that an in-house lawyer is on their team. I don't want names now, but how many of your legal counsel, whether they be in-house or outside, are risk averse? [audience laughter].

Okay, that's good. Okay. When I was general counsel at DePaul, I used to tell my lawyers, "We are not going to be the office of no, where good ideas go to die."

I think in this area it is so important to have a lawyer who can rock and roll with you, who can be flexible. It's always an issue of assessing the level of risk you're willing to tolerate. And lawyers—God love them, I'm a lawyer too -- it's easy to default to “don't do it" when it looks tough but you're really going to need lawyers who are going to be flexible and try to understand where you're trying to go, particularly in this area. So Art, will you talk a little bit about leadership, the kind of leadership we need at institutions in this challenging era?

Art Coleman: So I think it's a really important question at this particular moment in time. When I think about the work ahead and when we are doing work with both institutions and national organizations on this front that we work with, I'm lifting up two things. Yes, of course you need the traditional legal policy review, audit, make decisions, figure out the calibration, what's your risk of tolerance. All of that is work that will happen, I think you need to get ready for that.

But certainly in the wake of the court opinions, this is going to be a moment of psychology as much as it is a moment of policy compliance. The effects will be felt far and wide if the decisions are as bad as we think. And you can look at Prop 209 reverberations in California or Prop 2 in Michigan or other states where votes like this have happened.

And my biggest concern from multiple conversations on the ground with institutions is, how are we addressing the particular needs and perspectives in the moment for our students, faculty, staff and alumni of color, in particular, who potentially feel like, "Gee, I really don't belong or I'm not welcome?" And so I think we've got to be really attentive to this moment, of taking care of our community in the wake of a decision.

And part of that for me implicates getting ready for the decision. Have conversations with faculty leaders or maybe faculty broadly, student leaders, students broadly, maybe some alumni groups to say, "This is what's coming and here is how we are getting ready. We're going to be proactive even as we are navigating to and through a decision that we think will have negative consequences." And I think getting ready for the messaging post-decision implicates a need for engagement with the community pre-decision.

José Padilla: Ishan, can you talk about some of the more practical things that you are doing right now while we're waiting for a decision?

Ishan Bhabha: Absolutely. From working with institutions and having literally calls almost every day as we help institutions work through this, I think the unfortunate truth is the devil is really in the details. You have to get deep into how your admissions process works. And I will tell you that if you speak to folks in the admissions office, you hear one thing and then if you actually look at the documents, see that the trainings, the ways applications are assessed, the databases in which application rankings are made, you see a very different story. So the danger of an overreaction, or frankly, an underreaction is not really understanding the process.

So that's number one. You really need to pull apart the process, understand how race intersects with the process, where does it intersect and how does it intersect? So you know what things you might need to change as a result. So that I would say would be number one.

Number two, as Art spoke about, this is a moment where leadership in higher education and staff in higher education are going to have to account to a huge number of stakeholders. And so a communications plan immediately when the decision comes out from the president or chancellor, how you're going to deal with be public sector that she or he is going to have to address, how you're going to deal with the board of trustees, students, alumni, applicants, the community in which the institution exists. I think a robust communications plan is critical. Why is that the case? Because I think that whatever policies you put in place afterwards, I think it is irresponsible not to look at them in a new legal environment where there is greater legal risk.

The law is going to be adverse. And the statements made by university or college leadership will be used by those who would like to attack whatever this latest stage is as evidence of an intent to defy the Supreme Court. And so you need to be not only very careful of the programs you put into place and how you design it, but you need to be careful of the words you use to describe it because those are exactly the things that will latched onto in any future cases. So that's the second thing.

The final thing I think is really looking at— and already institutions do this, as I said— the two other sides of the admissions system: how do you shape the class that applies and how do you yield the class that you let in? Those are areas of opportunity. Again, the door may close on that too, ultimately, but it's open right now. And so, a real focus on that, I think, is correct.

José Padilla: Before we go to questions, is all hope lost? and I want all three of you to comment on this. We'll start with Shannon.

Shannon Gundy: Absolutely positively not. This isn't the first challenge. It's not going to be the last challenge, but the work still has to be done because what we're doing is important. It's critical to education for everyone. So the work has to be done. And I've reached the point now where yes, I'm tired, yes, I'm frustrated, I'm angry, I'm tired of this. Really, can we just do our work? But the way that I've chosen to approach it is it's sort of like a game at this point. It's like, "Okay, so you're telling me I can't do it this way. How can I do it? How can I solve this puzzle? How can I be creative while working within the constraints of the law and being very public about the fact that I'm working within the constraints of the law, but how can I move the puzzle pieces differently and come up with the same outcome?" So hope is definitely not lost. We're going to keep doing the work that we need to do and we're going to do it well.

Ishan Bhabha: Yeah. So I absolutely agree. I don't think all hope is lost. I think it's important to be realistic. And if you look at the Michigan and the California examples where affirmative action or race conscious admissions is illegal as a matter of state law the diversity in the classes matriculating goes down. And I think that is an important reality and it's one that I think it's important for people in positions of leadership to brace their stakeholders for, so that you don't face outrage based upon a misunderstanding.

By the same token, I absolutely agree with Shannon that there are lots of areas of opportunity. It requires work, it requires rolling up sleeves. It requires really figuring out what are the institutional priorities? How are they going to be manifested in a new admissions process or a new matriculation process, a new advertising process for the institution to bring applications in? That's work, that's time. That's not another thing you want to have on your desk. But I think that's the reality and I think there are lots of creative ways that institutions can still fill priorities like diversity in the post-decision world. It'll just be different, it'll be harder work. But I definitely agree. I don't think now is the time to think that diversity in universities and colleges is over.

Art Coleman: And I would just echo the sentiment of my colleagues, to affirm, hope still exists. And I would say in a broad context, that really depends so much on the messaging coming from presidents and provosts, that leadership, that we will continue to do the work. Shannon said this very eloquently a few minutes ago, we will continue to do the work that is mission central to us. As you are thinking through your post-decision messaging, not just, “yes, we will comply with the law," but what is your commitment, notwithstanding what is a legal ruling that may be negative in certain limited context, about your broader commitment to DEI.

And I would say too, it's an opportunity and a window of time where—lawyers are very guilty of this, we get so caught up in the details and the nuances of the legal decision and the policy implications—you can breathe, step back, and recalibrate your entire design around the enrollment policy and practice or at least consider a recalibration. The decisions you made five or six years ago with respect to policies and practices that had some negative effect on racial diversity might have been made where you had a very robust consideration of race in admissions and financial aid for instance. Tomorrow, that may not be the case. Does that decision from five years ago still hold? I think those are worthy conversations to have with respect to early decision, legacy, test use, transfer policies and the list goes on and on.

So let's not get so caught up in the details of a legal analysis, as important as that is, without stepping back and reflecting on the broader equity design implications about who we are as institutions at this moment in time, I will simply lift up NACAC and NASPA who published a report early last year, I think, that really took a step back to say, "how can we reimagine financial aid and admissions from a purely equity lens, to get provocative thinking going in the field?" So it's a very good resource to consider in your context.

José Padilla: Just be creative. So after the Gratz and Grutter decisions we had this victory. And then the state of Michigan passed a constitutional amendment that banned race conscious admissions and you would think there, all hope was lost. Well, I was then a member of the board of directors of the University of Michigan Alumni Association, which fortunately was separately incorporated from the University of Michigan. So the alumni association stepped into the breach. Naturally, it didn't admit students but what it could do is create what's called a lead scholars fund in which it gave race conscious and ethnicity conscious financial aid to students who have been admitted to the University of Michigan. And they also started providing support programs for students of color and they could do that and get beyond the reach of the scrutiny of this constitutional amendment.

So, at least for the state schools, many of you have foundations that I imagine are separate. Those may be avenues to fill a certain breach caused by this case. There's all kinds of things you can do if indeed it happens the way we can anticipate.

Any final comments before we turn it over to questions? Okay.

Audience member Q: This is such an excellent session and so properly timed. And Art, I like so much the idea that we need to look back at decisions we've made that impact diversity, that perhaps at this time when this decision lands--the legacies and all kinds of things—we might want to review again. But of course, Pell students are disproportionately minority students, and one option certainly is to think about the potential impact on the matter we're discussing of increasing the effort for Pell students. And I wonder if the panel would comment on that?

Art Coleman: Yeah, I would just say it's a good point. I think many institutions that are already engaged in this space are not just pursuing racial diversity. It's a broad-based diversity. It includes lots of things like low income. And I would actually say, just to put one finer operational point on it, many institutions have experience with not just looking at low income but low wealth status, which tells you something consequentially different with racial implications than just income. And so there are degrees of difference here that are worth thinking about.

Audience member Q: So two questions. You talked about being mindful of statements and my question is about threading the needle: being clear that you want to maintain institutional commitment, but not having that language used against you in the courts. If you could speak to that? And the second question is about alumni associations and being able to use solicitative means, there's some concerns about that as well. Could you say more about the way Michigan dealt with that?

Ishan Bhabha: Sure. So obviously they'll be those with much finer degrees of communication knowledge than me. But what I would say on that note is I think there's going to be an immediate pressure on leadership to basically say, "I don't care what the Supreme Court said." And I think a statement like that is irresponsible and I think it is really what those who would attack institutions post-June are looking for. And so I think it's really about nuance, it's not giving into the immediate demands of faculty and the students or whomever, who are going to be outraged, who are going to want to hear that. I think it's about saying, look, we are living in a new legal paradigm. We will of course follow the law. Nonetheless, diversity and inclusion continue to be core values of this institution and we're going to achieve our goals in a way consistent with law, something like that.

I just think it's really important that these things are prepared beforehand because as soon as the decision comes out, university leadership is going to be called on within hours, probably within minutes to give interviews or to give a statement, and that statement needs to be very carefully thought.

Art Coleman: So let me just say I couldn't agree more with what Ishan just said. Obviously students will not be on campus the last week in June. By the way, the decision could come down much sooner, but we don't know when it's coming down. Conventional wisdom is it's going to be toward the end of June. You need to be thinking about your online strategy for reaching students, as well as your on-campus strategy.

José Padilla: With respect to the University of Michigan, again, the alumni association was separately incorporated, but I also know that, for example, at Valpo, and I also believe that the University of Colorado system, they are all connected to the university. So it's hard to create the kind of separation necessary. But if you're fortunate enough to have a separate alumni association or a foundation, I think that opens all kinds of avenues with respect to the financial aid part, and possibly with respect to student support. But you just have to make sure that your lawyers can see this as legally separate.

Audience member Q: Our development officers who are securing scholarships and the individuals who are giving generously to those scholarships will specifically say they want it to be for an African American in medical school or a Hispanic student or even a male in nursing school. Can you give some advice about whether they should be changing how they're talking to donors about the limits that they can put on what those scholarships are used for?

Art Coleman: It is a key part of the inventory that with institutions I'm working with, we are pulling that list now to try to identify however those dozens or hundreds of scholarships, what are the ones that would likely touch race. And I think there's a good shot you're going to be subject to the same general prohibitions that apply to admissions when you see a decision potentially framed as broadly as we think this one might be.

I will say there may be distinctions in degrees of risk tolerance where some institutions are going to say, "I'm waiting for the court to tell me as a matter of scholarships before I change my scholarship policy." I will just offer as a reminder, back in the good old days when I was at the Department of Education, we put forth its first Title VI race conscious financial aid guidance. For that guidance, we had no cases of scholarships to rely on with respect to diversity. What did we do? We did what lawyers do every day. We turned to first principles on similar cases and we turned to Bakke to lift the admissions principles and then adapted them into financial aid. We still don't have financial aid and scholarship cases dealing with diversity today.

José Padilla: I think one of the things that will happen is—I hate to talk about in this way—but I think you may have a little more wiggle room when it comes to Latino students because again, you would never say it's going to go to a Latino student, but you could say something to the effect of a second language was spoken in the household.

Ishan Bhabha: That makes me think of another example in this respect. In addition to the 95 percent of my time working with colleges and universities, I do also work with corporations who are dealing with DEI issues, because there's a lot of that, too, now. And corporate America is likewise being sued by the very same groups and the very same lawyers who are bringing the cases against Harvard and North Carolina. One of the things that you see is corporations are becoming more sensitive to the fact that if previously there was a mentorship program or a scholarship program that was limited to individuals of a certain race for ethnicity, there may be some ways of recalibrating the program so it's not fully limited, but it still goes to the same principle.

Similarly, students who have shown a concern for the inequity suffered by underrepresented minority communities may be from the community, or they may not be. And I think you have to live those values, and then over a course of five years, it cannot solely be underrepresented minorities who receive it. But I do think there are ways with relatively small distinctions that are meaningful to achieve the same outcome.

José Padilla: Along those lines, at Michigan, there was a law school scholarship that was dedicated to a Latino student and again, they had broad criteria. Now, I don't know how they got around this because the constitutional amendment was already there, but in any event, there was one year where an Anglo student got the Juan Tienda Award, because they had written the requirements so broadly that a Anglo student could be eligible to apply, and in that particular case, that student, I think they got it through the language issue.

Audience member Q: Suppose I'm at an institution that's fortunate enough to have lots of scholarship money, and it accepts and has scholarships that are, shall we say, race limited, but the people who are actually deciding how to disperse the scholarship money aren't aware of which pool it's coming from. In other words, my institution is not tying the dollars received from the donor, that are in fact race-limited, to the allocation to a student. Is that different? Does that help?

Art Coleman: If I understand your question, I think you're articulating some version of a pooling-and-match strategy by which you're pooling all dollars, including those coming from race targeted or race conscious scholarships. You are making fundamental decisions about who gets the award independent of their race. And then you're allocating back out with respect to the races. I will tell you, it is a model colleges and universities are using pretty robustly. I know of no case law on it, but there is a logic to the design that I think helps mitigate or insulate you from legal risk because the actual decision- making is a race neutral decision, not a race conscious decision.

Ishan Bhabha: And to the same point, it's also harder for an individual who did not receive money allocated from one scholarship fund, but nonetheless had his financial needs fully met from a pool, to actually articulate what the harm is.

Art Coleman: But by the way, just to put the fine point on that. If I sue because I don't like the race conscious scholarship and then the race conscious scholarship is gone, I've just shrunk the total financial aid available to all students. I've not done anything to really help myself.

Audience member Q: This might be a bit nuanced, but I'd love to hear you talk about it. There are two public schools in the nation that offer a tuition waiver for Native American students who are enrolled tribal members. And there are several states now that have moved in that direction, some sort of tribal affiliation. Thoughts about what might be the implications for the decision on that?

Ishan Bhabha: I think it's a very busy time here, because obviously the Brackeen v. Haaland decision is going to play a huge role in the topic, what a Native American classification actually is. Is it a racial classification, political classification? So I think you're really going to have to view the upcoming court decisions with the context of Brackeen. I know about this because one of my partners argued Brackeen. I don't spend much time reading Supreme Court decisions, I have three young kids. But I do think that, yes, it's going to be a big question and I think Native American referencing is absolutely another thing that's going to be seriously looked at by those challenging these issues.

José Padilla: That's going to have to be the last question. Again, I want to thank Shannon Gundy, Ishan Bhabha, and Art Coleman, for giving us their expertise and experience. I'll also thank Peter McDonough from ACE who has done a fantastic job being our shepherd. And I want to thank you all for coming, because obviously this is an important issue and we are really going to have to address it.